‘I do not want Charity I want my rights’: Perceptions of state support in the Ministry of Pensions Archives

Posted by Jessica Meyer

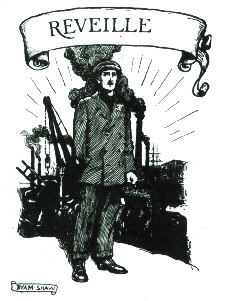

In her post last week on Active History, Brittany Dunn noted that, in their approach to the Canadian Board of Pension Commissioners, ‘ex-officers typically wanted to avoid dependence on the state, feeling it compromised their status as self-sufficient providers.’ The records of the Ministry of Pensions in Britain demonstrate that this feeling was equally widespread among British pensioners, although it was by no means confined to the officer ranks. Men such as R.A.M., who served in the ranks of the Machine Gun Corps expressed similar anxieties over the implications of applying for or receiving support from the Ministry of Pensions for their status as independent men.[1] As historians of masculinity in the period have shown, the role of financially independent head of household was central to ideas of respectable masculinity across the classes in Britain in this period.[2] And, as in Canada, the ultimate goal of physical and financial independence was promoted by the British state through publications such as Reveille, the magazine ‘devoted to the disabled sailor and soldier’, edited by John Galsworthy and containing informational articles on ‘Restorative Treatment’ by Sir John Collie and ‘Physical Education’ by Col. Netterville Barron, as well as stories by notable authors such as Rudyard Kipling and J.M. Barrie.

In her post last week on Active History, Brittany Dunn noted that, in their approach to the Canadian Board of Pension Commissioners, ‘ex-officers typically wanted to avoid dependence on the state, feeling it compromised their status as self-sufficient providers.’ The records of the Ministry of Pensions in Britain demonstrate that this feeling was equally widespread among British pensioners, although it was by no means confined to the officer ranks. Men such as R.A.M., who served in the ranks of the Machine Gun Corps expressed similar anxieties over the implications of applying for or receiving support from the Ministry of Pensions for their status as independent men.[1] As historians of masculinity in the period have shown, the role of financially independent head of household was central to ideas of respectable masculinity across the classes in Britain in this period.[2] And, as in Canada, the ultimate goal of physical and financial independence was promoted by the British state through publications such as Reveille, the magazine ‘devoted to the disabled sailor and soldier’, edited by John Galsworthy and containing informational articles on ‘Restorative Treatment’ by Sir John Collie and ‘Physical Education’ by Col. Netterville Barron, as well as stories by notable authors such as Rudyard Kipling and J.M. Barrie.

Figure 1: Reveille: Devoted to the Disabled Sailor & Soldier, edited by John Galsworthy, August 1918.

What is interesting, therefore, in both the Canadian and British cases, is the mobilization of the language of charity by men in their justifications for delays in applying for or reluctance to receive a pension. J.H.H., for example, wrote that ‘I do not want a pension. I want to be clear of the whole thing … and get well again’, while G.H.B. claimed ‘It is a hell to write asking for this favour.’ C.E.E. was, perhaps, the most explicit, stating that, in asking for a lump sum payment rather than a pension, ‘I do not want Charity I want my rights.’[3] In their denials of wishing to be in receipt of charity and their insistence on their desire to be working to support themselves rather than asking for state aid, these men implied that a war disability pension was, in fact, a form of charity rather than a statutory right or a duty owed them in return for the physical or psychological sacrifice for the State.

Of course, not all pensioners viewed their pensions in this light, with many seeing the financial support they received as justly deserved in return for their sacrifice of bodily health and autonomy for the state. Interestingly, however, the evidence from the British pension records points to advocates on behalf of pensioner, rather than pensioners themselves, voicing this opinion. Thus C.E.E.’s father pointed out that his son had ‘faithfully and worthily done his duty to his King and Country and is now in need of their care.’[4] Nonetheless, the prevalence of the ‘pension as charity’ argument, particularly as articulated by pensioners themselves, is a reminder of just how radical the idea of the welfare state was in the interwar period. Even with the expansion of state surveillance and demands for citizen sacrifice that total war had entailed, the idea of the state repaying that sacrifice with financial security and medical aid could still be cast as voluntary, not by the state itself but by those who had made the sacrifice. In Britain, the rise of a predominantly apolitical charitable sector supporting disabled ex-servicemen, as discussed by Deborah Cohen,[5] served to reinforce ideas of personal independence as the mark of respectable masculinity and, with it, claims to full citizenship. It would take another world war, and further sacrifices on the part of citizens, this time many with the right to vote that they had not previously had, for the idea that that very citizenship was the determining right to state support, rather than such support being available only to those who were able to best perform their appropriate independence and work ethic for the audience of the state and society.

[1] Memorandum, 18th August, 1918, PIN 26/19894, The National Archives, London.

[2] John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999); Ross McKibbin, Classes and Cultures: England 1918-1951 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Julie-Marie Strange, Fatherhood and the British Working Class, 1866-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Laura King, Family Men: Fatherhood and Masculinity in Britain, 1914-1960 (Oxford: Oxford University Pess, 2015).

[3] Letter to Director General of Awards, 2nd July, 1921, PIN 26/21791, The National Archives, London; Letter to Ministry of Pension, 11th March, 1922, PIN 26/21205, The National Archives, London; Letter to Ministry of Pension, 9th April, 1920, PIN 26/21580, The National Archives, London.

[4] Letter to Ministry of Pensions, 6th January, 2915, PIN 26/21580, The National Archives, London.

[5] Deborah Cohen, The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).