In the Archives: The Mundane, the Heartbreaking and the Absurd.

Posted by Alexia Moncrieff

I have now completed six research trips to the National Archives in Kew. Along with getting to know the train line between Leeds and London rather well, I have also developed a perverse joy and an unwarranted sense of pride when I manage to time my commute from central London to Kew such that I can step off the Piccadilly Line at Hammersmith and walk straight across the platform, directly on to a District Line train. It is certainly preferable to the usual interminable wait for a tube to Richmond. These research trips, of which there will be many more over the course of my four years as part of Men, Women and Care, vary between the mundane, the heartbreaking and the absurd.

Collecting information in archives can be boring. The archive we are working with, PIN 26, contains 22,756 files and we are taking the information from all of them and creating a database from it. In practice, that means we are each spending time in London photographing page after page after page of material in the files. This is the mundane work of history. Thankfully headphones are allowed in the reading room so the boredom can be alleviated by listening to music (though dancing along in your chair will incur raised eyebrows from those around you). I also listen to podcasts and my archive favourites include The Allusionist, 99% Invisible, Chat 10 Looks 3, The Guilty Feminist, and Mortified, but I warn you that comedy podcasts are dangerous. Giggling to yourself elicits a similar response from those around you to when you bust a move.

When I actually stop to read the file contents I am confronted with two things: first, the broad array of wounds treated by the military's medical services, and second, the intimate details of people’s lives. Popular memory of the war has reduced the wounds of British soldiers to shell-shock and shattered limbs. While these were common (leaving aside the problem of terminology for what I’ll broadly term ‘war neuroses’) they were by no means the only forms of wounding. Over the past few months I have come across cases of stricture of the anus, oesophageal cancer, alopecia, hyperthyroidism, tubercular epididymitis, asthma, meningitis, glaucoma, dementia, pleurisy, and dysentery.

Not only are personal medical histories and information about how war-related wounds can alter the daily lives of veterans included, these files also illuminate the domestic impact of war service. These stories can be heartbreaking. Like the man in receipt of a 40% pension who worked to supplement his income but was not able to fulfill his job responsibilities so subcontracted some of the work to a local lad. This left the ex-serviceman with not enough money each week to purchase sufficient food. He could not afford not to work, yet his physical limitations and the aggravation of his disability at work caused lasting problems. Or there’s the woman who wrote to the Ministry of Pensions in 1961 returning her pension book as she had heard through her brother-in-law about the death of her husband, a husband who had abandoned her and their three children more than thirty years earlier.

The correspondence in these files can be incredibly moving and it makes me glad I am undertaking this research as part of a collaborative team, enabling us to share the emotional weight of these files. The recent session on self-care at ‘Who Cares?: The Past and Present of Caring’ has made me wonder what historians do with this emotional burden, especially when working alone or away on research trips and separated from those with whom they might ordinarily discuss their archival finds.

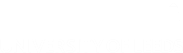

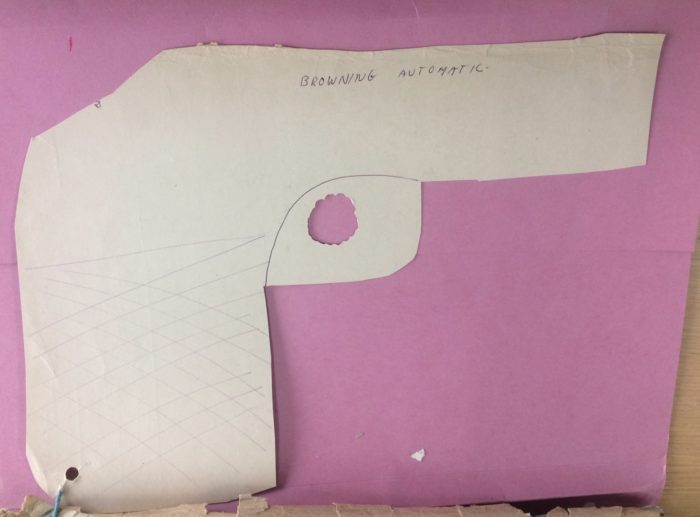

Then there are the absurd moments in the archives – the ones that baffle. One of the joys of archival work is finding the weird and wonderful things people have scribbled in the margins of history. For those on Twitter, the hashtag #marginalia is replete with examples of doodles and some delightfully snide commentary. On my most recent trip to the archives I had an absurd find of my own. Each PIN 26 file has a cover that shows a history of Ministry of Pensions officials who accessed and added information over the life of the claim. In this instance it had been cut into a shape, not immediately obvious to me:

But once I turned the page it became obvious that the page had been cut to the shape of a handgun. Detail and a label had also been added in what looks like ballpoint pen:

This begs the question: why? A question to which I do not have an answer. The National Archives is vigilant about checking what researchers take in and out of the reading room so I think it unlikely that a member of the public did this when reading the file. Scissors and pen are both banned. The man whose file this is was wounded by a gunshot wound to his left leg so perhaps a Ministry of Pensions or National Archives employee was bored one day and felt like illustrating it? Maybe the rest of the page was damaged and was subsequently trimmed down to its current size before someone noticed the shape and added some detail? Whoever did this appears to have gone to the trouble of ensuring that the information on the file cover has been unaffected by their artistry. Whatever the reason for the alteration of the file, it provided me with some baffling entertainment and an object for my neighbours and me to bond over as we scratched our heads and tried to work out why someone had cut a file cover page into the shape of a gun.

This is my experience of hiding away in archives but I am interested in hearing about yours. How do you make the mundane moments in the archives less soporific? How do you cope with the sometimes distressing information in the files you examine? What weird finds have you come across in an archive? I would love to hear about how others ‘do’ history. Let me know on Twitter (@HistoryNerdess) or email me: a.moncrieff@leeds.ac.uk.