Family Life

Andrew McCormick lived in Scotland and enlisted in the army straight after the First World War broke out, serving in both the UK and France until August 1919. He sustained a gunshot wound to the buttocks and in 1924 was awarded a pension for emphysema and bronchitis following pneumonia, but it was the mental repercussions of the war that had the most powerful impact on his wife.

In March 1925, he was admitted to Montrose Asylum for melancholia, where he stayed until July of that year. His wife was awarded a pension on his behalf as, according to the Ministry of Pensions, his mental health caused his total incapacity at the time. However, money was often the only form of help for wives of veterans; the state failed to address the psychological toll on the women whose husbands had physically returned from the war, but emotionally remained distant [Meyer, 2004]. After Andrew was released from the asylum and deemed capable of looking after himself, he fell into an erratic cycle of alcoholism to cope with his depression.

Whenever Andrew binged on alcohol, sometimes for up to three weeks or more, his wife was terrified of him, often escaping to her sister’s house during these periods. When drunk, Andrew tried to abuse his wife multiple times, and was violent towards members of the public, once being arrested for disorderly conduct. While the social stigma towards mental health at the time indicates a lack of support for mentally ill veterans from the public, even family members failed to help as well. Mrs McCormick pleaded with her brother to help Andrew, but he refused, claiming her husband was too dangerous [Reid, 2010]. His father attempted to support him, employing him at his tailor business, but Andrew spent over half of the year he was employed there either fully or partially unfit for work due to his depression and alcoholism. Consequently, his father fired him, as his unpredictable mental state was difficult to deal with and negatively affected his business, describing his son’s predicament as incurable. Without the sympathy and sensitivity of his father as his employer, Andrew had low hopes of finding other work.

While he was known to be a gentlemen before the war, post-war his maid described him as often short-tempered and anti-social, disturbing the maid’s work to the point that his maids would often quit, showing the instability of his home-life. Whenever Andrew went through prolonged periods of sobriety, he is described as morally sound and a decent man. However, in those times his wife would live in daily fear and anticipation that he would relapse, once stating that she would have no idea how to prevent his self-destruction, reflecting the burden on the wives to save their husbands; a full-time role after the war [Meyer, 2009]. Families coped with these pressures in different ways, including through divorce. Ultimately, Andrew’s deteriorating mental health led to his wife’s own nervous breakdown.

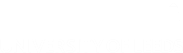

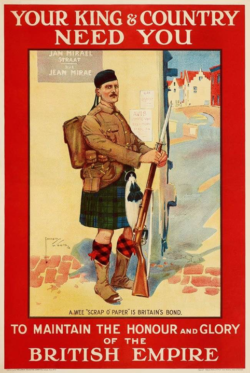

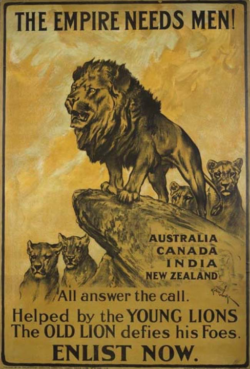

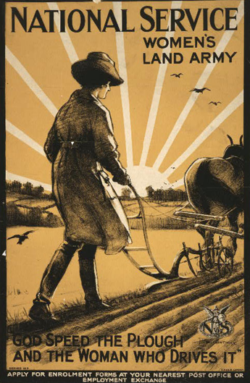

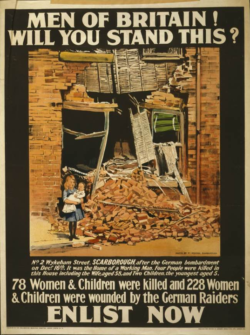

Take a look at the following propaganda posters from the First World War. What do they imply about the role of women, children and fathers during the First World War?

1914, by Lawson Wood, Imperial War Museum.

www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30809

Poster, 'The Empire Needs Men!' Artist - Arthur Wardle; March 1915; United Kingdom, Straker Brothers Ltd; printing firm. Parliamentary Recruiting Committee.

Museum of New Zealand. March 1915.

https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/1020691

1914. British Library.

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/women-britain-say-go?mobile=on

National Service Women's Land Army. "God speed the plough and the woman who drives it" / H.G. Gawthorn ; D.A. & S. Ld. London.

Library of Congress. 1917.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003675370/

Credit: Library of Congress / Commons.

For the glory of Ireland / Hely's Limited, Litho, Dublin.

1915.

Library of Congress.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003668400/