Veteran Employment

Arthur Powell was born in Welshpool, Wales, in 1894. He is one of many veterans who struggled to return to employment once discharged. Both before his enlistment in 1910, and after he was discharged in 1919, Arthur worked as a shoemaker in his family firm. On his discharge documents, he stated that he had no disabilities. However, in 1925 he began to apply for pensions for a whole host of conditions, including neurasthenia, malaria, bronchitis, an ankle injury, and fever.

When asked by the Ministry of Pensions why it had taken him six years to apply, he wrote on his appeal application, dated 7 July 1925, that 'I would have applied for pension, years ago. But hoped I would have recovered long ago. I do not get a big wage. And am married & have two children. And the time lost, means we all have to suffer.' This heart-wrenching message is indicative of an experience that was very common; the struggle to return to civilian life, and become the male breadwinner that interwar Britain valued so highly [Koven, 1994].

Arthur’s files show many of the insecurities that accompanied this mentality; he initially did not apply for any pensions, aspiring instead to support his family independently. However, in 1925, when his father gave Arthur the family business it began to lose money, potentially linked to the wider economic downturn experienced during the interwar period.

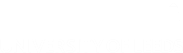

Data taken from Mitra, Patrick, and Naveen Srinivasan, ‘Interwar Unemployment in the UK and the US: Old and New Evidence’, in South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance, 5 (2016), 96-112

It is clear from his appeals that his neurasthenia had been significantly affecting his life, with his employer, who was also his father, testifying that he was frequently unable to work. His choice to wait for five years before seeking any help demonstrates the power that social stigma had over the lives of First World War veterans. Prevailing social norms dictated that a middle class family would consist of a male breadwinner and a female homemaker; indeed, employment, and earning wages was seen as a masculine sphere. Disability, especially mental disability, was also seen as a weakness, and therefore not compatible with masculinity [Reid, 2010]. It is telling that Arthur initially tried to claim for malaria due to a series of shivering attacks, but multiple blood tests contradicted this as a diagnosis. However, these attacks are also a symptom of neurasthenia and the Ministry of Pensions decided that this was what he was actually suffering from. This suggests that he was keen to disguise the fact that he had a mental disability, perhaps because they attracted more stigma than physical disabilities in a society that had a limited understanding of mental health [Reid, 2010].

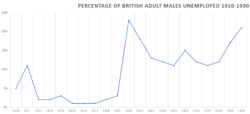

These charts show that large numbers of veterans faced unemployment and even homelessness. Poor relief was aid given by the state to the most desperate of people, and vagrants were both unemployed and homeless [Levine-Clark, 2015].

Data taken from Levine-Clark, Marjorie, Unemployment, Welfare, and Masculine Citizenship: “So Much Honest Poverty” in Britain, 1870-1930, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

How do you think that these veterans felt, having risked their lives, only to return to poverty?

The following images demonstrate the efforts made by the government to alleviate this issue. What might this show about the status of veteran employment in Britain?

Certificate of King’s National Royal Scheme for disabled service men, 1921. The scheme incentivised employers to give jobs to veterans. Copyright: ©TNA (Catalogue ref: LAB 20/366) http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/twenties-britain-part-one/employment-of-disabled-servicemen/

Cabinet memorandum on the employment of ex-servicemen in the building trades, 1921. Copyright: © TNA (Catalogue ref: CAB 24/127) http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/twenties-britain-part-one/unemployment-for-ex-servicemen/